Create

Imagine two cups.

Both are precisely designed and skillfully made: one by expert hands; the other with modern machines. They are handsome to the eye, inviting to the touch. They each hold the mysteries of a creative vision, yet they are immediately familiar in what they do for us — in caliber and in function, they appear to be equals.

Both are designed solutions that represent the modern mastery of their times.

Which one is crafted?

Craft

A process requiring deep skill, a mastery of technique, to make something that is at once useful and special.

Craft is an amazingly flexible, broadly dimensional idea. It’s rare to use one simple word to mean so many things: unlike any other discipline, craft is a verb, a noun, an adjective. We craft an object. We recognize goods by their particular type of craft; we appreciate the craft in them, the care of their crafted detail. Craft suggests quality, worth, character, training, history. It is the abiding human response to create the best version of any goods that we need or want, in the most thoughtful and often the most innovative way that we can.

In the built world, craft and creativity are the means by which we resolve how to make things better — always changing, always seeking to improve a form with new tools or materials, for richer outcomes. A cup is just a cup without that essential signature. We feel it missing when it isn’t present.

Craft was historically and still is frequently equal to the hand-made — and at times, in purist terms, we speak of “the hand” of the product or the maker. It’s the local expression of a natural material or trade, beautifully coaxed into form by a talented craftsperson. Many design and architectural modes are disciplines of craft, from textiles to woodworking, pottery to cabinetry, fashion to furniture. These are also called the “applied arts” as there is so much fundamental art in them, and even in the title of artisan.

Though culture is always evolving, we believe in a set of enduring traits that are always present in extraordinary examples of craft.

We apply them to the products we make now, and we learn from them in all kinds of crafts that inspire us from the past.

Today, that skill has spread across all forms of new and old applications; it has merged with the artistmaker, one who makes something useable. Craft has become identified with a particular design lifestyle — a counterrevolution in response to the impersonality of the mass-made. As with the movement towards customization, we have our craft beer and artisanal finishes and limited edition furnishings. In modern life the romance of craft has reclaimed this nostalgia, for a simpler, smaller and more meaningful, more select, less cluttered and anonymous world. And by this measure, it would seem that mass production, the advent of the machine age and the digital age, the world of the technical and the rise of the technician, are forever the antithesis of craft.

But that’s not the whole story. Or even the right story. Because craft is modern in every age. And technology has always been its tool. Craft is made of ingenuity as much as tradition.

Creators, craftspeople and innovators have always applied both mind and hand to the best technology or tools available at the time, in the quest to make things better. Old “technologies” get replaced with new ones; sometimes, with resistance. Oftentimes, tried-and-true techniques survive and co-evolve with other crafts over many generations. Handspun and handwoven fabrics coexist with textiles from 19th century looms, and with ever more intricate programmed looms, new invented materials, 3D printing. So, it’s just that what we may think of as “technology” is the latest chapter of imagination and discovery that allows us to do things we couldn’t have done or even thought possible before.

And in this way, modern craft doesn’t just mean new interpretations of vintage forms. Using machines and engineering, craft is the bridge between art and science, continually uniting creativity with practicality. It’s the leading edge of what’s possible to create … with the evolving technology that can realize ever more complex visions of what can be designed and built. It is a rich continuum of human problem-solving and expression. It’s not a chasm between then and now.

Many of the products we love most are in fact a combination of generations of craft — from the hand to the machine to the mind. We think of it all as human-made. And that’s what we’re inspired to create.

The culture of modern craft is central to our point of view. We apply it to all of our work with the most inventive mindset and emergent technologies that we can engage, to bring new meaning to the idea of what a crafted object can be. This is the future that we envision and want to solve for — to create the most delightful, intuitive and highly considered products that connect us to an ever-changing world.

Beauty and Material

The Ingredients.

Humans are wired for beauty. We intuitively understand elegant proportions that create balance; symmetry that is present or intentionally absent; the contour of a shape, its lightness or density, its angles or curves; the saturation of a color or the tactile expression of a surface. We associate these qualities in the built world with simple and complex forms in nature, and though beauty is subjective, we know it when we see it.

All these properties of perception are also elements of design. And as in a recipe, they’re ingredients. In craft, they are combined and then honed into something inviting, functional, memorable.

Beauty is expressed in the unique way each material is refined into a form.

It’s a natural instinct to want to interact with beautiful things, to make them our own. And the medium that holds this sensory beauty is the material something is made of. Craft has always been the province of materiality. Historically it is linked with elemental materials — intrinsically alluring wood, leather, stone, fiber, clay, glass, metal — that offer beneficial characteristics. These are the materials discovered and prized over generations for the many ways that they can be adapted, at once useful and attractive.

Now the materials available to us are rapidly evolving, and with them, the ways that they can be manipulated to form new shapes or offer new properties. Polymers, composites and elements like carbon fiber, as well as organic materials shaped by new machinery, can carry the lightness of silk, the seamless expanse of a tall tree, increased strength to weight ratios, better moldability, scalability, durability. The new materials of craft may not have the perfect imperfections of the natural world. But they can be crafted with trailblazing intricacy, again and again.

Curiosity and Knowledge

The Spark.

The inspiration to make a new product often starts with a set of questions. What is the need? How can we improve on the performance or value or comfort in this category of familiar objects? What’s this new material or technique that we can play with? Where will this creative process take us? Who can teach us?

Curiosity comes from a mindset that wants to open new doors and find different answers. In craft, curiosity isn’t satisfied with reproduction; it’s the antidote to complacency. It is the laboratory in which we choose to learn and experiment. And from those explorations we build the knowledge of how to make things — and create new ways to make them better. Better means we can improve the making-of, the manufacturing process; it can also mean the product itself is better, a more enhanced or pioneering version of what’s come before.

Curiosity enables the pursuit of knowledge that makes our products more thoughtful and human.

Yet curiosity is also full of interest and even reverence for how things work and how they were previously made — what tools or techniques are most tried-and-true as they are, and which can be reinvented, or cross pollinated, with new ones.

Craft depends on knowledge to become more than a generic commodity. For knowledge is more than the question or its answer. It’s not data, not solely measurement or method, or a formula. Knowledge is the lived experience of all the information we gather, where insight can grow out of trial and error as we stretch our craft. The quest for knowledge is the constant that gives a special product its spark, with a sense of discovery that we can feel.

Innovation and Technology

The Tools.

Tools determine the progression of craft. That’s because tools extend the ability of the hand, farther and farther into new capabilities; yet, they are always a vehicle for what both the mind and the hand want to make. In every age, almost any tool’s reason for being is innovation.

Innovation makes it possible for new ideas, attitudes and abilities to emerge, out of the same skills and needs we might already have. So we invent better tools, using or advancing the technologies of the time. Technology is simply the applied science of how we create.

And the more sophisticated the tools, the more potential creative disruption in the object. The more disruptive the object, the more we adapt, evolve, and hopefully, delight in what can be solved around the next corner.

Innovation is why we equip ourselves with technology — to remain relevant, to explore and inspire.

Innovation in craft is not always about complexity. And technology is often developed not only to augment but also to simplify. The purest and most seamless forms are oftentimes the hardest to create; the most elaborate problems frequently have the most elegant, simple solutions. This evolution isn’t just about aesthetics, it’s centrally about the process of how things are made.

Craft naturally starts with visualizing; translating from the mind through a set of tools. As new technologies emerge, paper and pen, compass and blueprint, give way to computer-aided drawing, and then again, to coding — allowing ever more unusual forms to be modeled, more engineering problems to be solved in 3D to 4D, mass customization to open new doors, new materials to become programmable and have memory. A building gains impossible curves, folds and textures; a chair can be machined with exquisite, continuous detail or a customer’s specific choice of profile.

Rather than being craft’s opponent, technology builds alliances. Together, the programmer and the scientist team with the designer to expand what it means to be a craftsperson — tailoring sophisticated machines to execute a most human creative vision.

Mastery and Heritage

The Pioneers.

Learn the rules so you can break them. This maxim celebrates the role of practice and learning, of continuously honing skill toward the mastery of one’s craft. It is the human element in the story of how craft becomes culture — transcending form and mimicry, as people develop such command of their medium that they can throw the rules away and invent something new.

The union of culture and craft is readily apparent in the product of a master. We are drawn to the intangible quality of talent that fuels extraordinary interpretation; and like beauty, we know mastery when we encounter it. It never goes out of style.

Mastery and heritage endure in the culture of craft to show us where we’ve been, so we know where we’re going.

Mastery is built on dual elements of time — the time it takes to acquire expertise, and the longer term over which a level of mastery becomes the standard. Time is where heritage exists in craft, connecting us to earlier customs and ultimately making certain things timeless. For what we consider today as heritage or heirloom was, in its origins, the work of nonconformists and visionaries who built a new layer of ideas or technical innovation atop the methods they had learned. We celebrate the people who’ve who made new connections between cultures, mediums and materials, and taught those around them how to rethink what was possible.

From musicians to potters, chefs to jewelers, winemakers to dancers to woodworkers, such virtuosity elevates the humanity in stretching old skills to express a different future. Their remarkable technique is the true translator of the technology — the instrument — they employ. Newer heritage in disciplines of computing and engineering may yet last as long and produce, in their own way, as much amazing artistry.

What Makes Craft

These four traits constantly combine, evolve and inform what we can create in the culture of modern craft

The Ingredients | The Spark |

The Tools | The Pioneers |

Case Study

Print-to-Pattern

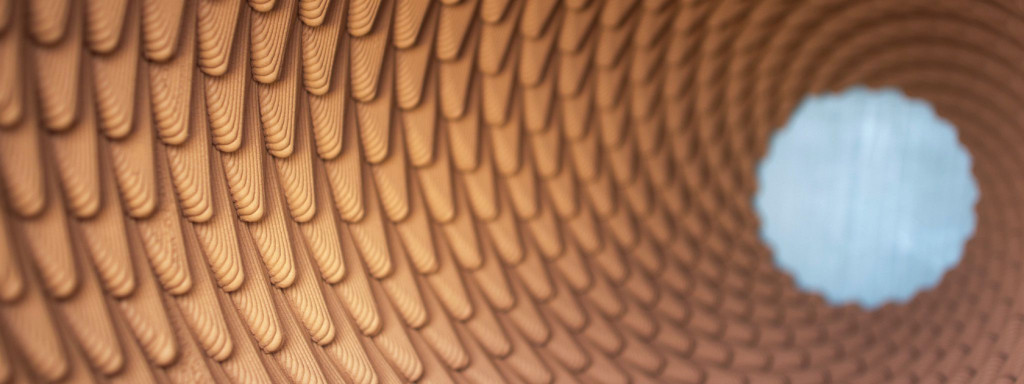

One of the perennial challenges in craft is how to apply a linear pattern onto a three-dimensional curvilinear form. Especially with textiles, this is the constant manipulation at the heart of dressmaking and tailoring as well as upholstery.

Resolving the natural disconnect between a flat bolt of fabric and a volumetric piece of furniture has until now been the province of the expert artisan — one who has a deep mastery of how to cut, drape and sew a pattern across intersecting planes and seams. In addition, the more involved the form, the greater the waste, because so much cutting is required into a pattern to find exactly the right junctions for assembly.

Accordingly, human skill, time and material are all spent at a high rate to craft a perfect piece. This type of work ultimately increases costs, limits availability, and lowers yields of valuable material. It can often take as much as 2 ½ times or more yardage than a piece of furniture needs to correctly match a pattern across seams.

A common consequence of this challenge is lower aesthetic quality. This happens in examples of upholstery where a pattern does not align — with a visually jarring effect. Alternately, creative choice may become limited, as solids or simpler patterns are substituted to assure a more successful product.

We can take a patterned fabric and arrange it wrong, so that when it’s cut and upholstered it looks right.

The Coalesse Design Group was curious about this increasing tension between an age-old technique of manufacturing and whether there could be new ways of inventing a fabric that would allow for a continuous pattern to be upholstered more efficiently, across even the most complex pieces of furniture.

The method and the material couldn’t change; so, something else had to.

“We’re often playing with ideas that look at our heritage and the irreplaceable value of certain crafts, but which then use technology to actually keep those things alive,” says John Hamilton, Director of Global Design, Coalesse. “For upholstery, we knew we would still have to apply the same amount of care and handwork to get to a beautiful piece of furniture.

“Effectively what we’re doing is reverse engineering, where we start by designing the pattern wrong. We take it apart and put it back together out of order, so that the upholstery comes out right,” laughs Hamilton, explaining how elaborate and unrecognizable any pattern work will appear on the pre-cut fabric. But in this way, each panel can be nested efficiently into every other, dramatically reducing waste and cost, while increasing productivity and creativity.

With the Print-to-Pattern prototype, any pattern for any piece of furniture may soon be possible with much more freedom of expression — embracing innovation to reimagine the most bespoke qualities of fine upholstery for a wider audience.

The Ingredients

Beauty and Material

The Spark

Curiosity and Knowledge

The Tools

Innovation and Technology

The Pioneers

Mastery and Heritage

We need them all to make things, better.

Join Coalesse in exploring the rich mix of hand, machine and mind in the culture of modern craft.